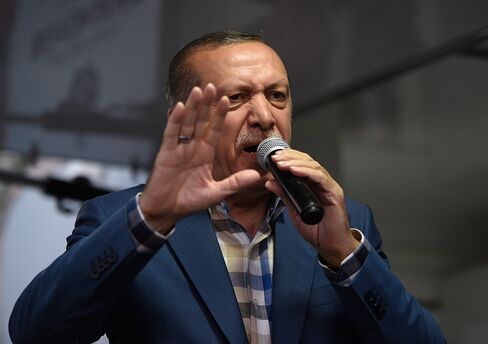

The political career of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been shaped by military coups, real or imagined, for more than four decades. Friday’s attempt is likely to prove the most consequential, and potentially empowering, of them all.

Whatever goals the rebels had, they may have ended up securing Erdogan’s position at a time of multiplying challenges to his popularity: Islamic State terror attacks, a war with militant Kurds, a failing foreign policy and weakened economic growth.

When the coup attempt was at its height on Friday night, some of Erdogan’s most ardent supporters heeded his call to take to the streets, facing down the guns and tanks of the soldiers. There was no such public show of support for the rebels, even from those in despair over Erdogan’s increasingly authoritarian rule.

As a result, the officers will have encouraged Erdogan, 62, to intensify his drive to change Turkey’s political system from a parliamentary to a presidential democracy, accelerating the concentration of power in his vast new presidential palace.

“Erdogan will use the sympathy the coup creates for him to his advantage,” said Henri Barkey, director of Middle East studies at the Wilson Center in Washington. But he warned, too, that there were risks for Erdogan and Turkey: The coup was also a sign of deep unhappiness within the military, and if the president presses too hard with purges against his perceived enemies, it could prove a pyrrhic victory.

“He will be more paranoid so he is likely to go hard with his purges, and in the process hurt a lot of people,” said Barkey. “Nobody will come out of this well.”

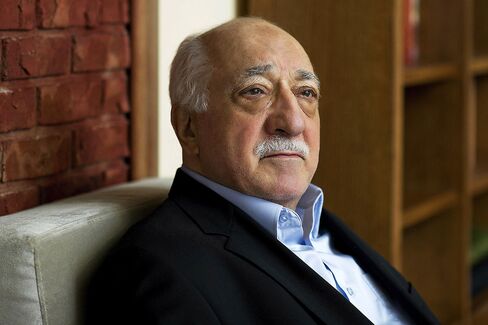

Friday night’s effort to seize power, which Erdogan blamed on a former ally turned enemy, U.S.-based preacher Fethullah Gulen, wouldn’t be the first coup to create political opportunities for him.

The son of a domineering Istanbul ferry captain, Erdogan entered politics in the 1970s. At the time, the 50-year old Turkish Republic had just endured a second coup by the military and was in a state of near anarchy. Ultra-nationalists, communists and, to a lesser extent, Islamists fought in the streets, leaving an estimated 5,000 dead.

Erdogan joined the Islamists. Two of his friends were killed in the violence — one by a bomb, another shot — he recalled in a 2011 interview. At the same time, he had a job at Istanbul’s transport authority, but after a third military coup, in 1980, he had to resign. The new boss, an army colonel, ordered men to shave off their beards, considered signs of religiosity — and Erdogan refused. The new regime also banned the Islamist political group to which he belonged, the National Salvation Party.

Fan Mail

The army, with its secularist agenda, was a natural enemy to Erdogan. But the coup and repression that followed also contributed to a shift for him and his fellow Islamists, who began to temper their religious radicalism to survive politically. They embraced electoral politics; by 1994, Erdogan was elected mayor of Istanbul, the country’s largest city and commercial heart.

Erdogan’s term as mayor was interrupted by a further intervention from the armed forces — the so-called “post-modern” coup of 1997, in which military commanders listed their complaints about the Islamist-led coalition government in a memorandum, forcing it to resign. In the purge that followed, Erdogan was jailed — for reading out a poem that compared minarets with bayonets.

Erdogan’s four-month incarceration only boosted his political appeal. He was inundated with fan mail and gifts while in prison, according to an aide at the time, Huseyin Besli. He cut a CD of his poetry readings. After his release, Erdogan co-founded the Justice and Development Party, or AK Party, which explicitly accepted the secular nature of the Turkish state, helping it win a wider following. By 2002, it was in power.

Fantasy Plot

From the moment Erdogan took charge, however, he appeared fearful of falling victim to yet another coup, perhaps understandably given the history. Those fears came to a head in 2007, when the AK Party put forward then-Foreign Minister Abdullah Gul to run as president. The army objected, describing itself as the “absolute defender of secularism,” in a move reminiscent of previous coups by memorandum. This time, the army fell short.

Facing down huge secularist demonstrations, Erdogan called snap elections at which the AK Party increased its parliamentary majority. The new legislature elected Gul as president, and Erdogan emerged even stronger, the military’s weakening grip having been exposed.

Immediately, prosecutors targeted the top brass. One case alleged that the armed forces had planned a coup against the AK Party government early in its term. The alleged plot, codenamed Sledgehammer, was a fantasy — the key evidence had been fabricated — and in 2014 the convictions were eventually thrown out. Many officers were released, but the phony coup cases had already served their purpose. Swathes of the military were decapitated, clearing the way for less militantly secularist generals.

When the Fethullah Gulen movement, Erdogan’s allies against the army, turned against him in 2013, he again alleged a coup attempt. In response to charges of corruption against his government and family, Erdogan mobilized a purge of the judiciary, police and other institutions, to remove Gulen supporters he accused of instigating the graft probe.

Since Erdogan blamed Gulen for Friday’s failed coup attempt, which according to the government left almost 200 people dead, another crackdown on the group’s supporters has begun. More than 2,800 military personnel were arrested during raids on Saturday and a similar number of judges and prosecutors were removed from their posts. Gulen and his group denied involvement and condemned the coup, while Erdogan’s government began topressure the U.S. for his extradition.

Since Erdogan blamed Gulen for Friday’s failed coup attempt, which according to the government left almost 200 people dead, another crackdown on the group’s supporters has begun. More than 2,800 military personnel were arrested during raids on Saturday and a similar number of judges and prosecutors were removed from their posts. Gulen and his group denied involvement and condemned the coup, while Erdogan’s government began topressure the U.S. for his extradition.Appeals from foreign governments and civil-rights groups for Erdogan to soften the country’s sweeping anti-terrorism laws, ease restrictions on media and return greater independence to the judiciary are also likely to receive increasingly short shrift.

None of this will be welcome news for investors, even if the much greater turmoil that would have followed a successful coup would have been worse, said Tim Ash, a strategist at Nomura International Plc in London, in a research note on Saturday. Friday night’s turmoil took 4.6 percent off the value of the lira, the steepest decline since 2008.

“What I find remarkable in all this, is that this group of military personnel, Gulenist or not, actually thought that they could succeed,” Ash said.

Instead, they may have made Turkey’s strongman stronger still.

[Source:- Bloombing]