It is the silence after a storm. The markets are shut and villagers are sitting in the shopfronts, huddled in groups. Young boys stand guard at roadblocks, made of stones, bricks and chopped trees. There is no phone connection, cable TV, local newspaper or the Internet. At some places, power has been cut off. Having failed to quell the mass protests following the killing of Kashmiri militant Burhan Wani, even police, paramilitary and Army have been withdrawn, to lessen the chances of a confrontation.

However, in the complete blockade encircling south Kashmir, there is no shortage of news. It comes by word of mouth, and it only serves to fuel a demand now heard all around: azaadi.

“Only azaadi,” says Abdul Rashid, a schoolteacher in Urwan Poshwan village. “Don’t write we asked for government probe into killings of our young men or sought any concessions from Mehbooba Mufti or her government. For the last several years, we have tried everything. We held on to straws, hoping for resolution of the Kashmir issue. We put our hope in talks. We put our hopes in the promises of politicians. But now we are ashamed of having trusted the lies of the Peoples Democratic Party, like we once trusted the lies of National Conference.”

Beneath the debris of police stations, paramilitary camps and government buildings, destroyed by protesters in the last week here, lie the ruins of this narrative of a middle ground, of the healing touch, of slogans like “goli se nahi boli se (with dialogue, not bullets)” that the PDP has crafted since its inception in 1999.

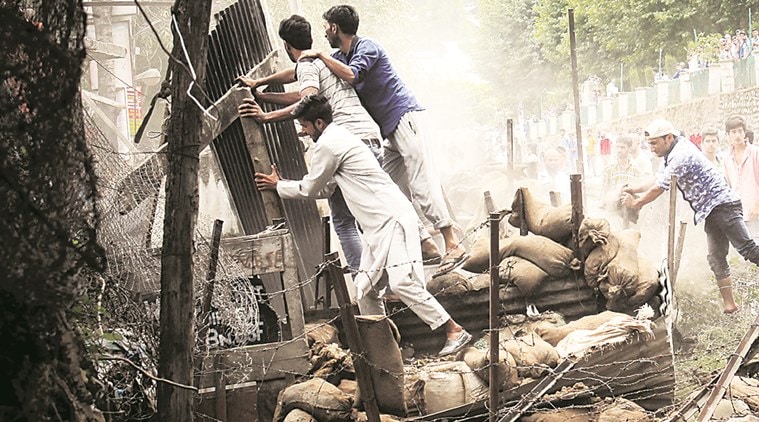

Protesters attack a security bunker in north Kashmir’s Bandipora district on Monday.

Protesters attack a security bunker in north Kashmir’s Bandipora district on Monday.

South Kashmir has been the PDP’s political bastion, with its top leaders billing the party’s soft separatist position of self-rule as an “achievable political goal”, between the “idealistic idea of azaadi” and the call for “integration into the Indian Union”. In the days since Burhan Wani’s killing, that ground is slipping fast from beneath the PDP’s feet.

Like in 1990 when “azaadi” was a rallying cry across Kashmir, the story on the ground here is again black and white.

Urwan is a tiny hamlet in Pulwama district, 20 km from Srinagar city. Unlike many neighbouring villages, Urwan did not have a “martyrs’ graveyard”. Last Sunday, a part of the village graveyard was “reserved” when 15-year-old local boy Irfan Manzoor Malik was buried there.

“Irfan is our first martyr,’’ says Bilal Ahmad, 22, a student. “And we know now that we will need a martyrs’ graveyard.”

He recalls that on that Sunday, villagers had gathered for another day of protests. “A CRPF convoy passed by and we shouted slogans and threw stones at them. They started firing and we ran away. In an alley, we saw Irfan lying in a pool of blood. He was hit by only one bullet, in his head,” says Ahmad.

Son of the village baker, Irfan was in Class IX. Irfan’s grandfather Abdul Gani Malik (80) sits on the verandah of their single-storey house with the neighbours. “They killed a child… There is no pain greater than losing your child in such a brutal way,” he says. “It has opened our eyes regarding those who had promised us greener pastures during the elections.”

There is “no ambiguity” now, agrees Altaf Ahmad. “No one among us is the PDP or NC now. We all want azaadi.”

Pushing aside his hookah, Irfan’s grandfather leans forward to add that he had nine grandchildren, of whom only eight are left. “Each of them is a Burhan now. Burhan too was harassed and tortured when he was a 15-year-old boy. His brother was killed. His father was beaten up. But he stood up to fight and showed us that all these, the PDP, NC people who claim to be our own, are nothing but agents of our killers,” he seethes.

Pulwama Deputy Commissioner Muneer-ul-Islam admits Irfan’s killing was “avoidable” and says he had raised it with the government.

Read | Kashmir unrest: Two more dead, PDP MLA ‘attacked’

A few miles away, in Kisrigam, villagers have put up a shamiana in the compound of the local school. For four days since the body of Zahoor Ahmad Mantoo was returned by police, boys in Kisrigam have been singing hyms on a loudspeaker.

Mantoo, a 26-year-old labourer, was last seen when paramilitary forces chased protesters in Awantipora on their way to attend the funeral of Burhan Wani.

Says his brother Irfan Ahmad Mantoo, “His body had torture marks on the head. He had gashes on his legs. We could not recognise him. But police said he drowned.”

At Mantoo’s home, village elders, leaning against the bare cement walls, worry about Mantoo’s widowed mother, four sisters and a disabled brother. “I am almost 100 years old,’’ Ismail Mantoo, a neighbour, says. “I have seen it before, and it repeats again and again. In my childhood, they said we would give you a sack of cotton and then they cut us with a sickle. Then they said we will give you sack of sugar and filled our lives with poison. Each time we believed their promises, and each time they betrayed us. Today it is Mehbooba Mufti sitting on that chair under whose stumps our boys are killed. Tomorrow it will be Omar Abdullah.”

People who canvassed for the PDP recently are among those sitting in the room. They say they have nothing to do with the party any more.

“The youngsters have shown us the way. They understand the lies better than the old men,” says Bashir Ahmad, 33.

The villagers are as angry with the Hurriyat Conference, saying the separatists have “plans only for themselves”. “This new movement has erupted in spite of them (Hurriyat),” a villager says.

Five kilometres away from Pulwama town, that is entirely shut, a group of boys has blocked the road at Tahab village. Over 180 people were injured in the first three days of protests here.

A government official, Fayaz Ahmad Sheikh says everyone is a part of the protests, that among those injured is a doctor. “There is a consensus that there is no option but to seek azaadi. The PDP had made inroads here, but it is over. We will show you how we have turned (last time’s) polling booth into a latrine here.”

Nine kilometres ahead, the paramilitary and Special Operations Group camp in Litter village, broken and burnt, stands testimony to this anger. After 28-year-old man Fayaz Ahmad Waza of nearby Niklora hamlet was killed in firing from the camp, the forces, sensing danger, abandoned it. The people ran it over with bulldozers.

[Source:-The Indian Express]