A startup on a shoestring budget is working to clean up the Android security mess, and has even demonstrated results where other “secure” Android phones have failed, raising questions about Google’s willingness to address the widespread vulnerabilities that exist in the world’s most popular mobile operating system.

“Copperhead is probably the most exciting thing happening in the world of Android security today,” Chris Soghoian, principal technologist with the Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project at the American Civil Liberties Union, tells Ars. “But the enigma with Copperhead is why do they even exist? Why is it that a company as large as Google and with as much money as Google and with such a respected security team—why is it there’s anything left for Copperhead to do?”

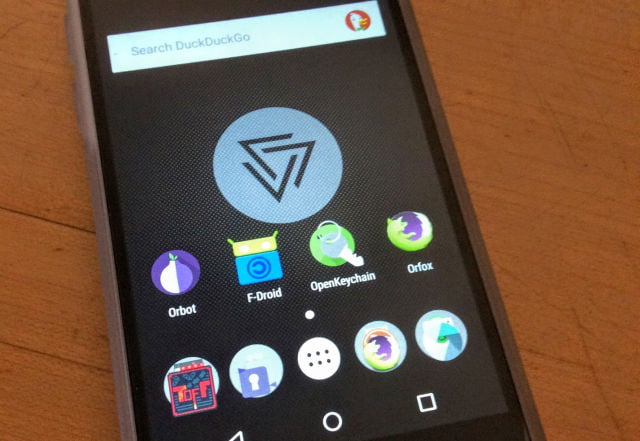

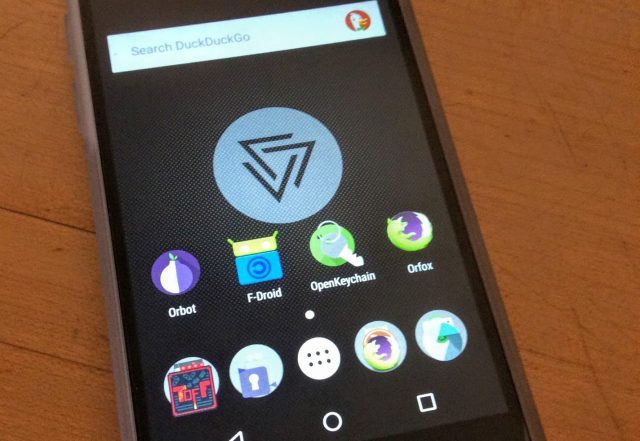

Copperhead OS, a two-man team based in Toronto, ships a hardened version of Android that aims to integrate Grsecurity and PaX into their distribution. Their OS also includes numerous security enhancements, including a port of OpenBSD’s malloc implementation, compiler hardening, enhanced SELinux policies, and function pointer protection in libc. Unfortunately for security nuts, Copperhead currently only supports Nexus devices.

Google’s Android security team have accepted many of Copperhead’s patches into their upstream Android Open Source Project (AOSP) code base. But a majority of Copperhead’s security enhancements are not likely ever to reach beyond the its small but growing user base, because of performance trade-offs or compatibility issues.

Dan Guido, CEO of Trail of Bits, has also puzzled over the vulnerability gap between the stock Android OS and Copperhead, and points out that the same could not be said for Apple’s iOS.

“If I had to imagine a world where there’s a Copperhead for iOS, I don’t even know what I’d change,” he tells Ars. “The Apple team almost always picked the more secure path to go and has found a way to overcome all these performance and user experience issues.”

A billion people around the world rely on Android to secure their digital lives. This number is only going to grow. How did we get here, and can Copperhead—or even Google—put out the garbage fire?

Contents

- 1 A deal with the devil

- 2 Just the Nexus, thanks

- 3 Most OEMs, for instance Motorola, do not ship the monthly security updates available from the AOSP. The business model for handset manufacturers ends with the sale to a consumer—at which point there are no financial incentives to maintain the devices for the next three years or so.

- 4 Grsecurity for Android

- 5

- 6 “N” to the rescue?

- 7 Can Copperhead succeed where others failed?

A deal with the devil

Google did a deal with the devil for market share, says Soghoian, who has described the current parlous state of Android security as a human rights issue. By giving Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and wireless carriers control over the end-user experience, Google allowed handset manufacturers to find ways to differentiate their products, and wireless carriers to disable features they thought would threaten their business model.

As a result, Google’s power over OEMs—such as Samsung or Motorola, who manufacture and sell Android handsets—consists solely of the Android license and access to the Google Play Store. The AOSP code base is licensed with Apache 2.0, and the kernel uses GPL2, which means there’s nothing stopping OEMs from deploying stock Android under a different name. But doing so would also mean losing access to the Play Store. This gives Google significant leverage over OEMs, but by no means absolute control—a competitor willing to forgo the Android trademark and offer customers access to their own app store, as Amazon has done, can walk away from the negotiating table with little to no consequence.

But Soghoian thinks Google isn’t trying very hard. The company could, he points out, demand that OEMs implement default full-disk encryption as part of the Android and Play Service licence terms. The company currently requires FDE when the hardware supports it, but extending that requirement to lower-end Android manufacturers might scare off a non-trivial fraction of OEMs—and that would hurt Google’s bottom line as an advertising company.

“The important thing to remember,” he says, “is that if Google goes nuclear and cuts an OEM from the Google Play store, and Gmail, and Google Maps, and YouTube, Google isn’t just hurting that OEM and its customers, it’s also hurting itself.”

“Every phone that doesn’t have YouTube and Google Mail and search is a phone that isn’t making money for Google,” he adds.

Copperhead, for their part, are not in the business of surveilling users in order to display targeted advertising and so are free to optimise Android for security. Their first challenge was to find a handset to support that offered regular security updates—no small ask.

Just the Nexus, thanks

Most OEMs, for instance Motorola, do not ship the monthly security updates available from the AOSP. The business model for handset manufacturers ends with the sale to a consumer—at which point there are no financial incentives to maintain the devices for the next three years or so.

Copperhead chooses to focus on optimising security for what they believe are the most secure handsets currently available: the Nexus devices whose software, if not hardware, Google controls directly, and which receive prompt monthly security updates.

“What we’re doing is starting with the Nexus; a pretty good starting point,” Copperhead’s Daniel Micay explains. “And we’re significantly improving the security of the operating system. We’re making a lot of under-the-hood changes and exploit mitigation to make it harder to exploit the vulnerabilities that are there.”

Micay’s goal is to port the Grsecurity and PaX patches to the Android Linux kernel, which would dramatically improve the security of all Android handsets, but this goal has been stymied by hardware woes—some of which not even Google appears capable of resolving, at least not on its own.

Grsecurity for Android

Grsecurity and its subset PaX harden the Linux kernel by making whole classes of vulnerabilities difficult, if not impossible, to exploit. Micay got his start as the Arch Linux maintainer of the Grsecurity and PaX patches for that distribution, and embraces the same security vision as Brad Spengler, who founded the Grsecurity project, and who has famously clashed with Linus Torvaldsover the years for the latter’s reluctance to ship a more secure kernel.

But Copperhead’s efforts to implement the Grsecurity patches for Android ran into a brick wall: Nexus devices, and indeed all newer mid- to high-end handsets, use the ARM64 architecture. While parts of Grsecurity have been ported to ARM32, little work has been done on ARM64, Micay says, leaving only a small subset of non-architecture-specific code for him to deploy. Porting Grsecurity to ARM64 is not a trivial undertaking—Micay estimates months of work for an experienced engineer, and Spengler and his team are not inclined to help without getting paid.

“Work on Grsecurity is still done in our free time,” Spengler says. “We don’t have any personal need for ARM64 support, so it’s not a priority for us in our limited time. I do have a development board on order, however.”

“We would have to research how KERNEXEC/UDEREF functionality could be implemented best on ARM64,” he adds. “Given our experience with that research and implementation on ARM, I’m not inclined to do more free work for the full-time funded upstream or multi-billion dollar corporations to rip off.”

Given the dramatic security benefits porting Grsecurity to Android would bring, and the relatively low cost of such work, Soghoian wonders why no one is paying Spengler and Micay to do so.

“In an ideal world, the US Department of Homeland Security would write a check to Spengler for $5 million and keep him busy,” Soghoian says, pointing to the Core Infrastructure Initiative (CII),founded after Heartbleed to take better care of critical open source security software like OpenSSL.

Because the Grsecurity project has the potential to positively benefit every Linux user on the planet—including servers, desktops, and more than a billion Android users—Soghoian argues that the project is the kind of thing the CII should be funding.

“The White House announced they were going to put more money into the open source community a few months ago,” he says. “It’s a totally realistic scenario.”

Soghoian also criticises Google for failing to step up to the plate. “Google could pay for the development of Grsecurity using the money found between the cushions of their sofa,” he insists. “This is not a big-ticket item in the grand scheme of Google’s budget.”

But even if ARM64 support were immediately available for the Android kernel, it would still be a year or two before Copperhead—or even Google—could deploy those patched kernels.

[Source:- ARS Technica]