In January 2009, a teen drama series took over South Korea. Boys Over Flowers was a Cinderella-esque tale of a less-privileged but feisty young girl who enrolls in a posh academy, where she encounters F4, a group of four boys who rule the school. The plot was simple: boys meet girl and a love triangle emerges. It was as hackneyed as it sounds, but nothing could predict the kind of response it generated not only in its home country, but in Japan, China, Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore and the Philippines. By the time the show wrapped up in March, its popularity had spread to places as far away as Gangtok in Sikkim, where two girls felt the ripples of Hallyu or the Korean Wave.

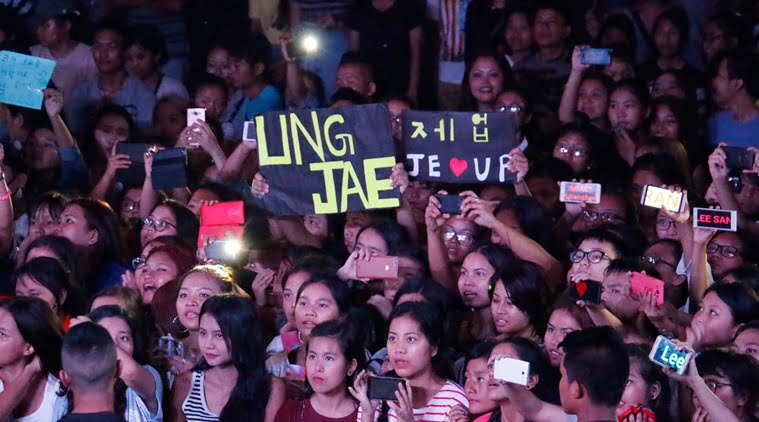

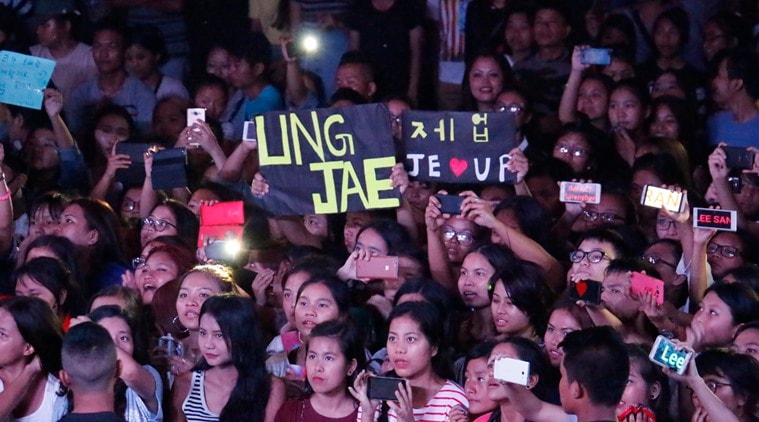

Fans in Aizawl, Mizoram hold up phones and placards during an IMFACT concert. (Source: KCCI)

Fans in Aizawl, Mizoram hold up phones and placards during an IMFACT concert. (Source: KCCI)

“It was like a virus and the whole school caught it,” says Roshni Pradhan, 20, a student at Manipal College of Physiotherapy. She recalls how a pirated CD of the show made the rounds of the school, converting students overnight into evangelical fans who began to casually pepper their conversation with Korean phrases: chincha (really), aish (oh no!), aaniyo (no), chingu (friend) — and, of course, saranghae (I love you). “Korean dramas also come with original soundtracks. I became a fan of the lead actors, who are also singers. I began to listen to their albums and I was hooked,” says Pradhan. So was the entire school, and consequently, Gangtok’s neighbourhoods, where entire families gathered to watch Korean dramas on cable TV with English subtitles.

But for Mahima Gurung, Boys Over Flowers and K-pop was more than entertainment — it changed her life. “I’ve lived in a hostel my whole life but I didn’t have many friends. I was shy and overweight. After watching Korean dramas and K-pop videos, I came out of my shell. I began to exercise, I coloured my hair. But most of all, I found new friends, other girls with whom I could share my passion for Korean pop culture,” says the 19-year-old who is studying geology at Sikkim Government College, Tadong.

If it weren’t for their examinations, both Pradhan and Gurung would have participated in the first-ever K-pop regional contest in Gangtok that took place on July 1. Nevertheless, that Friday, they joined over 1,000 fans who had trooped to Manan Bhawan, the secretariat building to watch IMFACT, a Korean “rookie” boy band, who would also judge the contest.

The boyband before their show in Gangtok. (Source: Express photo by Rinchen Dorjee Lepcha)

The boyband before their show in Gangtok. (Source: Express photo by Rinchen Dorjee Lepcha)

A 360-degree view and what you had was Oppa Gangtok style. Girls like Pradhan and Gurung had modelled their look on Girls Generation: poker-straight hair grazing over pastel blouses paired with jeans; faux leather jackets, blonde hair and a disinterested gaze — those girls were bringing home the vibe of rapper CL, K-pop’s “baddest female”. The boys were all BTS and EXO though — American football blazers, patterned short-sleeved shirts, skinny jeans — because, like, could you name any other boy bands that are hotter than them today?

Inside, girls held their arms over their heads in an M-shape, or joined their thumbs and index fingers to make heart signs, and as IMFACT executed a coordinated jump on stage, their screams reached fever pitch. Hysteria swept through the hall when competing dance groups got into formation for BTS’s Dope and Fire; adults chaperoning their wards looked dazed and sheepish in equal measure. The young fans, many of whom had travelled from Manipur, Nagaland and Mizoram, didn’t care. As far as they were concerned, it was the greatest night of their lives.

What did they like so much about K-pop? “Everything,” Pradhan and Gurung say in unison. Euphoria has reduced their vocabulary to “awesome” and “amazing” but when it comes to K-pop, it makes perfect sense.

What makes K-pop different from Western pop? Not much, considering how derivative the sound is, borrowing heavily from R&B, mainstream American hip-hop, trap and Euro-dance tropes. But a K-pop music video? That’s like an energy drink with multiple flavours. One swig and you’re transported to a high-definition, Technicolor universe where eternally youthful people with legs for days are dressed in the latest fashions, the newest hairstyle framing their delicate white faces, as they dance and sing about love, heartbreak, friendship and being young. Every album is based on a “concept”; so, sometimes they care about love, sometimes they don’t, sometimes life is dope, other times they’re jaded and want to break free. One thing is for certain: they don’t just look good, they look spectacular.

“The Korean artistes are pretty, stylish and so different from what we see on Indian TV, where everything is saas-bahu. There is only romance and fun in their shows or songs,” says Gurung, whose new and improved wardrobe includes distressed jeans and bright-coloured sweaters to match her ombre hair. She had taken down the photos of the bands and her “true love”, EXO’s 23-year-old baby-faced rapper Chaneyol, from the walls in her room because of the exams, but they are all up in the common room. There are lipstick marks and hearts drawn in red ink on the posters and lots of giggling as Gurung and Pradhan show us around — this is a giddy kind of love but with little fulfillment in sight.

Roshni Pradhan (second from left) and Mahima Gurung (third from left) and their friends make heart signs in front of their K-pop shrine. (Source: Express photo by Rinchen Dorjee Lepcha)

Roshni Pradhan (second from left) and Mahima Gurung (third from left) and their friends make heart signs in front of their K-pop shrine. (Source: Express photo by Rinchen Dorjee Lepcha)

Pradhan has taught herself a smattering of Korean, uses the Korean script on herFacebook profile, follows Oh Se-hun from EXO on Instagram, and has made friends with fans in Singapore and Malaysia who share her love of all things K-pop. Yet, she seems to admit that she won’t be living in the candyfloss bubble for long. “I feel that the course of our lives has already been decided. We’ll graduate in a few years, get jobs. I want to apply to Korean entertainment agencies but I fear that time has passed us by,” she says wistfully.

While Gangtok was chosen as the Northeast’s regional centre, K-pop has exerted a greater influence in northeastern states — Mizoram, Nagaland, and especially Manipur — for quite some time. “K-pop is as popular at home as Bollywood music, if not more,” says Adane, winner of the Gangtok round. The 16-year-old student from Don Bosco College, Maram, Manipur, travelled for nearly three days to perform at the show. And while she became a fan of the genre only a year ago, Manipur’s love affair with Korean pop culture goes back 16 years. In September 2000, the Revolutionary People’s Front (RPF), issued a blanket ban on Hindi, including Bollywood films and songs, to stop the increasing “Indianisation” of Manipur. The lack of local entertainment channels forced people to look eastwards.

If you lived outside of Manipur, you could tune in to watch Emperor of the Sea and A Jewel in the Palace, two popular Korean dramas that were aired on DD1 in July and September 2006 respectively. Boys Over Flowers gradually found its way to hostels in Kolkata, Bangalore, Hyderabad and Chennai, leaving many young women hopelessly in love with Korean “flower boys” or metrosexuals. “Korean men are portrayed to be as sensitive as women. It’s okay for them to cry. In Indian films and TV, men mostly come across as emotionless, macho types,” says Aarcha Kumar, 21, an avid “K-pop-er” in Bangalore since 2011.

K-pop fandom in India today is driven almost entirely online, especially on YouTube where Korean agencies post the latest music videos, and fans upload their covers of popular songs. The number of fans in the country runs into several thousands and they are spread over the Northeast, Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore and Chennai.

Fans take a selfie with members of IMFACT, a K-pop band, in Gangtok during the regional finals of the 2016 K-Pop India contest. (Source: Express photo by Rinchen Dorjee Lepcha)

Fans take a selfie with members of IMFACT, a K-pop band, in Gangtok during the regional finals of the 2016 K-Pop India contest. (Source: Express photo by Rinchen Dorjee Lepcha)

The fandom consists primarily of tweens and those freshly out of their teens, but is not limited to them. “There are K-drama fans of all ages, but not so for K-pop. That is not to say that the genre doesn’t have something to offer to the more discerning listener,” says Vibha Barrow, 35, an editor at Scholastic India, who has been a fan since 2005. “I liked what I saw when I first discovered K-pop. It is a very visually-appealing genre in terms of choreography and presentation, as well as the idols themselves. That leads to an obsession with fair skin, but I guess we have to acknowledge that that is a ubiquitously Asian problem,” she says.

“I’m glad there’s no age limit in the contest as yet,” says Bharti Gupta, 29, winner of the Delhi round and recent K-pop convert. To watch this petite north Indian girl belt out an Ailee song, about moving on after the end of a relationship, with gusto and flawless pronunciation was a surreal experience even for the 300-odd listeners who had flooded the basement of the Korean Cultural Centre India (KCCI) to watch 22 acts compete to win a spot in the Chennai finals. “I feel a connection with Korean culture, they have great respect for the arts. I know I don’t look like the typical K-pop artist, but the contest is a great opportunity for an Indian K-pop fan to represent the country,” says Gupta.

It’s a connection born out of the randomness of a wired, connected world; the serendipity that makes a young person in dusty Delhi sing of love in the language of Seoul’s streets. Still, K-pop would not have been here if not for one man.

***

“I had heard of how popular Korean dramas and K-pop was in the Northeast, but the rest of India seemed to be more aware of American music. So in 2012, I thought this could be a good opportunity to showcase our culture — why not have a K-pop contest in India?” said Pyoung, director of Korean Cultural Centre India (KCCI), as he paused to chat at the Gangtok show. This K-pop regional final was of particular importance to him — Cho Hyun, ambassador of the Republic of Korea to India, was a special guest. Not only that, he’s also invited Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) and Delhi-based Korean journalists to cover the show.

This wasn’t KBS’s first time to India to track the K-pop subculture. Last year, the network produced Dugeun Dugeun India (Fluttering India), a reality TV show that starred five of K-pop’s golden boys — Super Junior’s Kyuhyun, SHINee’s Minho, CNBLUE’s Jonghyun, INFINITE’s Sunggyu, and EXO’s Suho. The premise was to introduce K-pop to India but after four episodes that were ill-informed, not to mention borderline racist, the show was canned. This time, KBS has an opportunity to set the record straight.

On August 25, 2012, the first K-pop contest took place at KCCI in Delhi, a year after Pyoung took over as director, where only a handful of people took part. Pyoung had been warned. “They said Korean culture will not work in India because India has its own diverse, vibrant cultures,” he recalled. But he persisted, adding more cities each year and taking the contest to Dimapur in 2014, Aizawl in 2015, and now Gangtok. Last year’s winners, Frozen Crew, a dance group from Aizawl, represented India at the sixth K-pop World Festival in Changwon. This year’s edition is the biggest yet and contests were held in six cities — Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Gangtok, Patna, Bangalore — through July. The finals will be in Chennai on July 31.

“When we started out, we saw only participants from the Northeast, but I don’t think Korean culture is popular there just because of the physical similarities. As a Buddhist, I can trace my roots to India. There are many similarities between our eastern traditions, such as the importance of family and the respect to elders,” says Pyoung, who had extended his original three-year term in 2014 to another three years. If there’s something he’s learned on the way, it is this: you can always trust the fans. Case in point: Bangalore.

***

It has been five years since Jayashree N, 24, first heard Gajendra Verma’s Tune mere jana, a song whose video was inspired by K-pop singer Lee Seung Gi’s Words that are hard to say. “I was curious about the original song and searched for it. I became such a fan that I looked for all his work — his music, acting cameos etc. I ended up watching all his dramas,” says the software professional, who enrolled in Korean classes at Bangalore University last year. “There are many people in the South who are into K-pop, so I started a Facebook group and a WhatsApp group for Bangalore’s K-popers and the numbers are growing,” she says.

Jayashree’s efforts led the KCCI to include Bangalore in the list of regional contests last year. “They called me this year and asked if the fans could organise the event, I was like, this is what we’ve been waiting for,” she says.

The Bangalore round was won by Aarcha Kumar, who is headed to the finals for the second time. If she wins the India contest, Kumar will have to shoot a video for the Changwon contest; if she is selected, she will win an all-expenses paid trip to South Korea. A dusky girl, Kumar is not at all fazed by K-pop’s preference for white skin. “More than 95 per cent of the artistes in K-pop have very fair skin. But things are changing. Former Fin.K.L member and K-pop icon Lee Hyori is seen as a pioneer for darker skin (by Korean standards) in Korean pop culture. Michelle Lee, a Korean-African American woman, was a contestant on the first season of the popular talent search show, K-Pop Star. This year, an all-Black K-pop group called Coco Avenue was formed in the US,” she says.

This should give Pradhan some hope. As soon as her exams end, she will work on her singing and upload an audition video on the Korean agencies’ websites. “Thousands of Koreans apply every day and only a handful are chosen as trainees. I don’t know if I’ll match their beauty standards but I’ve got to try. I want nothing more in the world than to go to Korea. I want to see if it’s actually like what they show in the dramas — everything and everybody is beautiful,” she says.